The Meaning of IQ: Why Students and Teacher Want Change

You’re sitting in class when your teacher announces IQ testing next week. Your stomach drops. You wonder why this single number gets to define your intelligence when you know you’re smart in ways tests can’t measure.

The Meaning of IQ will show how traditional intelligence testing affects real classrooms and real lives like yours.

What You’ll Learn:

• Why traditional IQ tests miss important types of intelligence

• How current testing systems create unfair barriers for students

• Which alternative assessment methods better reflect your actual abilities

Your intelligence extends far beyond what any single test can capture. It’s time the education system caught up with this reality.

Understanding Traditional IQ Testing and Its Historical Purpose

How Standardized Intelligence Tests Measure Cognitive Abilities

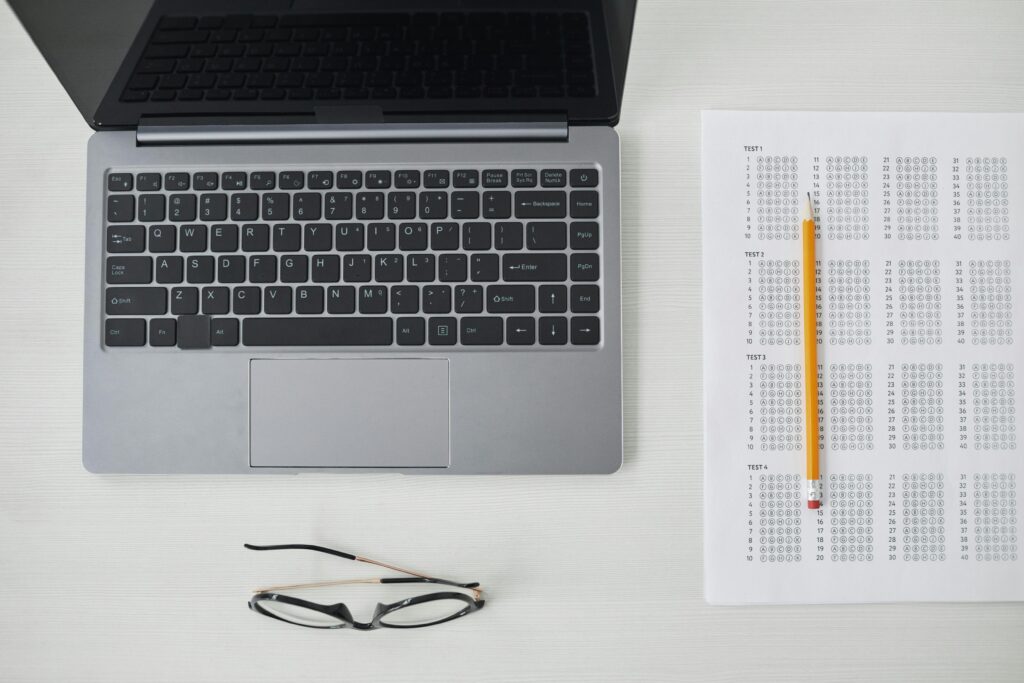

Your typical IQ test breaks down intelligence into specific measurable components. These assessments examine verbal reasoning, mathematical problem-solving, spatial awareness, and processing speed through structured tasks.

Most standardized tests follow similar patterns. You’ll encounter word analogies, number sequences, pattern recognition puzzles, and memory challenges designed to evaluate different cognitive strengths.

Core Components of Intelligence Testing

The Wechsler scales represent the gold standard in IQ assessment. You’re tested across four main areas: verbal comprehension, perceptual reasoning, working memory, and processing speed capabilities.

Each subtest contributes to your overall score calculation. Verbal sections might ask you to define words or explain similarities between concepts, while performance areas test visual-spatial skills.

Key Testing Components:

• Verbal reasoning through vocabulary and comprehension tasks

• Non-verbal problem-solving using visual patterns and sequences

• Working memory assessment through digit span and arithmetic challenges

The Original Intent Behind IQ Assessments in Educational Settings

Alfred Binet created the first practical intelligence test in 1905 to identify students needing additional educational support. Your modern understanding of IQ stems from this educational origin.

Schools initially embraced IQ testing as an objective method for academic placement. Educators believed these assessments could predict your academic success and guide appropriate instructional strategies.

Educational Placement and Resource Allocation

IQ scores traditionally determined your placement in special education programs, gifted classes, or standard academic tracks. School administrators used these numbers to allocate resources and design curricula.

The meaning of IQ in educational contexts centered on identifying cognitive potential rather than measuring actual achievement. Your score supposedly revealed innate learning capacity.

Original Educational Goals:

• Identify students requiring specialized instruction or support services

• Predict academic performance and guide educational planning decisions

Common Misconceptions About What IQ Scores Actually Represent

Many people believe IQ measures your overall intelligence or determines your life success potential. This oversimplification misrepresents what these tests actually assess and their practical limitations.

Your IQ score reflects performance on specific cognitive tasks during a particular testing session. Environmental factors, cultural background, and test-taking experience significantly influence these results.

The Fixed Intelligence Myth

One major misconception suggests your IQ remains constant throughout life. Research shows cognitive abilities can improve through education, training, and life experiences that challenge your thinking.

Cultural bias presents another significant issue. Tests often favor certain socioeconomic backgrounds and educational experiences, making scores less meaningful across diverse populations.

Limitations of Numerical Representation

IQ scores compress complex cognitive abilities into single numbers. Your creative thinking, emotional intelligence, practical problem-solving skills, and social awareness aren’t captured through traditional testing methods.

Common Misunderstandings:

• IQ scores predict career success or life satisfaction levels

• Higher scores indicate superior human worth or intellectual capacity

• Test results remain unchangeable throughout your lifetime

| Aspect | What People Think | What Tests Actually Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Intelligence Coverage | Complete intellectual ability | Limited cognitive skills subset |

| Score Stability | Fixed throughout life | Variable with experience and education |

| Cultural Fairness | Universal measurement | Culturally influenced performance |

| Predictive Power | Life success indicator | Academic performance correlation |

| Cognitive Scope | All thinking abilities | Specific testable skills only |

Critical Flaws in Current IQ Testing Systems

Limited scope of intelligence measurement ignoring creativity and emotional skills

Your child might excel at painting or understanding others’ emotions, but traditional IQ tests won’t capture these abilities. Standard assessments focus heavily on logical reasoning and mathematical skills while ignoring creative thinking.

When you look at what makes someone successful in life, emotional intelligence often matters more than raw analytical ability. Your ability to collaborate, empathize, and think outside the box gets completely overlooked in conventional testing.

Key Points:

• IQ tests measure narrow cognitive abilities, missing artistic and interpersonal strengths

• Creative problem-solving and emotional awareness aren’t evaluated in standard assessments

Cultural bias in standardized testing

Your cultural background significantly influences how you interpret and respond to test questions. Many IQ assessments contain references and examples that favor specific socioeconomic or ethnic groups, creating unfair advantages.

If you grew up in a different cultural context, you might struggle with questions that assume certain shared experiences or knowledge bases. This cultural loading skews results and doesn’t reflect your true intellectual capacity.

Key Points:

• Test questions often contain cultural assumptions that disadvantage certain groups

• Your background knowledge affects performance regardless of actual intelligence level

How test anxiety and environmental factors distort accurate assessment

Your stress levels on testing day can dramatically impact your performance, regardless of your actual abilities. When you’re anxious, your working memory decreases and problem-solving skills become impaired during the assessment.

External factors like hunger, lack of sleep, or distractions in your testing environment can cause significant score variations. Your mood, health status, and comfort level all influence results more than most people realize.

Testing conditions rarely mirror real-world problem-solving scenarios where you have time to think, access resources, and collaborate with others. Your performance under artificial time pressure doesn’t represent how you actually function intellectually.

Key Points:

• Anxiety and stress significantly reduce cognitive performance during testing

• Environmental factors like noise, temperature, and comfort affect concentration and results

The failure to account for different learning styles and strengths

Your brain might process information differently than the standardized testing format assumes. If you’re a visual learner, verbal-heavy questions put you at an immediate disadvantage regardless of your intelligence level.

Some people excel at hands-on learning but struggle with abstract theoretical problems presented in traditional tests. Your kinesthetic or auditory processing strengths get completely ignored in paper-and-pencil assessments.

The meaning of IQ becomes questionable when tests fail to recognize that intelligence manifests differently across individuals. Your pattern recognition might be excellent, but sequential processing could be challenging.

Key Points:

• Different learning styles aren’t accommodated in standardized IQ testing formats

• Hands-on and experiential learners face disadvantages in traditional assessment methods

• Multiple intelligence types remain unrecognized in conventional testing approaches

Key Points Summary:

• Traditional IQ tests measure only narrow aspects of intelligence while ignoring creativity, emotional skills, and practical abilities

• Cultural bias in test design creates unfair advantages for certain demographic groups

• Test anxiety and environmental factors significantly distort accurate assessment of cognitive abilities

• Different learning styles and processing strengths aren’t accommodated in standardized testing formats

• The meaning of IQ becomes limited when assessments fail to capture the full spectrum of human intelligence

Student Perspectives on IQ Testing Limitations

Increased Stress and Academic Pressure from Standardized Scoring

When you face IQ testing, you experience mounting pressure that transforms learning into a competition. Your worth becomes tied to numerical scores, creating anxiety that clouds your natural abilities and creative thinking.

Key impacts on student wellbeing:

• Test anxiety interferes with cognitive performance during assessments

• Academic pressure shifts focus from learning to score achievement

• Mental health concerns increase among students facing repeated evaluations

Reduced Self-Confidence Among Students Labeled with Lower Scores

Your self-perception changes dramatically when educators label you with lower IQ scores. These numbers create lasting damage to your confidence, making you doubt your capabilities across all subjects and activities.

Effects of score labeling:

• Students internalize negative beliefs about their intellectual capacity

• Academic motivation decreases following poor test results

• Social stigma develops around perceived intelligence differences

Limited Recognition of Diverse Talents and Abilities Beyond Test Performance

Your artistic skills, emotional intelligence, and practical problem-solving abilities remain invisible in traditional IQ assessments. The meaning of IQ becomes narrow, excluding your unique strengths and varied learning styles.

Overlooked student capabilities:

• Creative expression and innovative thinking patterns

• Leadership qualities and collaborative skills

• Hands-on learning and kinesthetic intelligence

| Limitation Area | Student Impact | Alternative Recognition |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Pressure | Increased anxiety and performance issues | Portfolio-based assessments |

| Score Labeling | Reduced confidence and motivation | Growth-focused feedback systems |

| Narrow Assessment | Missed talents and abilities | Multiple intelligence evaluations |

Teacher Concerns About IQ-Based Educational Practices

Pressure to Teach to Standardized Tests Rather Than Individual Student Needs

You face constant pressure to align your curriculum with standardized testing requirements that don’t reflect the true meaning of IQ or learning potential. Your classroom becomes a test-prep environment rather than a space for genuine intellectual growth and exploration.

This testing focus forces you to abandon creative teaching methods that actually engage students. You spend valuable time drilling specific test formats instead of developing critical thinking skills that truly matter for your students’ futures.

Key Challenges:

• Limited flexibility in curriculum design due to testing mandates

• Reduced time for project-based and experiential learning opportunities

• Administrative pressure to prioritize test scores over student development

Supporting Students with Varied Learning Capabilities

You struggle to meet diverse learning needs when educational systems rely heavily on traditional IQ measurements. Your students with different cognitive strengths often get overlooked or mislabeled based on narrow assessment criteria.

You see firsthand how some students excel in areas that standardized tests can’t measure. Visual learners, kinesthetic processors, and creative thinkers deserve recognition for their unique intellectual contributions to your classroom community.

Learning Diversity Issues:

• One-size-fits-all approaches fail many capable students

• Limited resources for alternative instruction methods

• Difficulty identifying true potential beyond test performance

Time Constraints Limiting Personalized Instruction

You barely have enough time to complete required curriculum standards, let alone provide individualized attention. Your days become rushed sequences of lessons designed to cover material rather than ensure deep understanding for each student.

You want to differentiate instruction based on each student’s actual learning profile, but administrative demands and large class sizes make personalized approaches nearly impossible to implement effectively.

Time Management Barriers:

• Overwhelming curriculum pacing guides restrict flexibility

• Large class sizes prevent individual attention

• Administrative tasks reduce actual teaching time

| Challenge Category | Impact on Teaching | Student Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Test Pressure | Narrow curriculum focus | Limited skill development |

| Learning Diversity | Inadequate support systems | Unrecognized potential |

| Time Constraints | Rushed instruction | Superficial understanding |

Alternative Assessment Methods Gaining Educational Support

Multiple intelligence theory applications in modern classrooms

You’ll find Howard Gardner’s multiple intelligence theory transforming how teachers assess your abilities today. Your linguistic, musical, spatial, and kinesthetic talents receive equal recognition alongside traditional academic skills.

Teachers design activities targeting your specific intelligence strengths. You might demonstrate mathematical concepts through movement, express scientific understanding through art, or showcase historical knowledge through musical compositions.

- Visual-spatial learners benefit from graphic organizers and mind mapping exercises

- Musical intelligence students excel when rhythm and melody enhance lesson content

- Bodily-kinesthetic learners thrive with hands-on experiments and physical demonstrations

Portfolio-based evaluation systems showing comprehensive student growth

Your learning journey becomes visible through carefully curated portfolios showcasing work samples, reflection essays, and progress documentation. You select pieces demonstrating growth across multiple subjects and skill areas.

Digital portfolios allow you to include multimedia presentations, video recordings, and interactive projects. Your teachers track development patterns rather than focusing solely on final grades or test scores.

Parents gain deeper insights into your learning process through portfolio conferences. You present your work directly, explaining choices, challenges overcome, and future goals while demonstrating ownership of your educational experience.

- Student-selected artifacts showcase personal learning preferences and achievements

- Regular reflection entries document thinking processes and problem-solving strategies

Competency-based learning frameworks replacing traditional grading

You advance through curriculum based on mastering specific skills rather than spending predetermined time periods studying topics. Your pace adapts to individual learning needs and comprehension levels.

Detailed rubrics outline exactly what you need to demonstrate for each competency level. You receive specific feedback about areas needing improvement rather than letter grades that provide limited information about actual understanding.

Your teachers focus on whether you’ve truly grasped concepts before moving forward. Retakes and alternative demonstrations become standard practice when you need additional time to reach proficiency standards.

- Mastery-based progression eliminates artificial time constraints on learning

- Clear performance criteria replace subjective grading practices

Key Points

- Multiple Intelligence Recognition: Your unique combination of intelligences receives equal validation and assessment opportunities across all subject areas

- Portfolio Documentation: Your comprehensive learning journey becomes visible through curated work samples and reflective documentation processes

- Competency Mastery: Your progression depends on demonstrated skill mastery rather than time-based advancement through predetermined curriculum sequences

Conclusion

Traditional IQ tests no longer capture the full picture of student intelligence and potential. You’ve seen how these outdated measures limit educational opportunities and fail to recognize diverse learning styles that define modern classrooms.

The shift toward alternative assessments isn’t just trendy – it’s necessary. You deserve evaluation methods that celebrate your unique strengths, whether you excel in creative thinking, emotional intelligence, or practical problem-solving skills that traditional tests completely miss.

Key Changes Needed:

• Replace single-score IQ tests with multiple intelligence assessments

• Train teachers to recognize different learning styles and capabilities

• Implement portfolio-based evaluations that showcase real student growth

| Current Problem | Student Impact | Teacher Challenge | Better Alternative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single IQ score | Limited opportunities | Narrow teaching focus | Multiple assessments |

| Standardized testing | Stress and anxiety | Pressure to teach to test | Portfolio evaluation |

| Fixed mindset | Reduced confidence | Limited flexibility | Growth-based measurement |

You have the power to advocate for change in your school community. Will you speak up for assessment methods that truly reflect the diverse brilliance you and your peers bring to learning every single day?

References

Howard Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences.” Center for Innovative Teaching & Learning, Northern Illinois University, n.d., https://www.niu.edu/citl/resources/guides/instructional-guide/gardners-theory-of-multiple-intelligences.shtml. Accessed 29 Nov. 2025

“Howard Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences.” Center for Instructional Technology & Training (CITT), University of Florida, n.d., https://citt.it.ufl.edu/resources/course-development/the-learning-process/types-of-learners/howard-gardners-multiple-intelligences/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2025

“Documents That Changed the World: Alfred Binet’s IQ Test (1905).” UW News, University of Washington, 14 June 2013, https://www.washington.edu/news/2013/06/14/documents-that-changed-the-world-alfred-binets-iq-test-1905/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2025

Silva, M. A. “Development of the WAIS-III: A Brief Overview, History, and …” Graduate Journal of Psychology, Marquette University, 2008, https://epublications.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1012&context=gjcp. Accessed 29 Nov. 2025

Ford, D. Y. “Intelligence Testing and Cultural Diversity: Pitfalls and Promises.” NRC/GT Newsletter, University of Connecticut, n.d., https://nrcgt.uconn.edu/newsletters/winter052/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2025

“Test Anxiety.” Academic Resource Center, Harvard University, 3 Oct. 2023, https://academicresourcecenter.harvard.edu/2023/10/03/test-anxiety/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2025

“Tackling Test Anxiety.” Learning Center, University of North Carolina (UNC), n.d., https://learningcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/tackling-test-anxiety/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2025

“Portfolio Assessment.” Office of Institutional Research & Assessment, University of Maine, n.d., https://umaine.edu/oira/assessment/portfolio-assessment/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2025

“Using Portfolios in Program Assessment.” Assessment & Curriculum Studies, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, n.d., https://manoa.hawaii.edu/assessment/resources/using-portfolios-in-program-assessment/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2025

“Competency-Based Education (CBE).” EDUCAUSE Library, EDUCAUSE, n.d., https://library.educause.edu/topics/teaching-and-learning/competency-based-education-cbe. Accessed 29 Nov. 2025.