Mastering High School Math: Tips and Tricks for Memorizing Math Equations

When an Equation Slips Away

You sit at your desk after school, pencil worn down to a nub.

You solved similar problems last week, yet tonight the steps feel slippery.

You whisper the formula, hoping it clicks back into place.

That pause between knowing and remembering is familiar to many high school students.

You want simple moves that bring equations back quickly, not long lists you ignore.

This article gives you practical ways to build memorizing math equations into your routine.

Why This Challenge Matters for You

Memory fades fast when you don’t revisit new material. (Wikipedia, “Forgetting Curve”)

You’re not worse at math — your brain needs the right timing to hold on.

Research shows that forcing yourself to recall beats rereading for lasting memory. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Short, spaced reviews protect what you learn better than one long cram session. (Psychological Science Observer)

That means small, regular practice can change how easily you retrieve formulas. (Lindquist et al.)

Quick truths to hold in mind:

- Memory fades without review, so timing matters. (Wikipedia, “Forgetting Curve”)

- Recalling is stronger than rereading for retention. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- Small, spaced sessions beat one long cram. (Psychological Science Observer)

Now that you see how memory works, you’re ready to build a plan that helps with memorizing math equations tonight.

Tips and Tricks You Can Use Today

- Short Study Sessions

- Retrieval

- Chunking Information

- Flashcards

- Mixing Problem Types

- Study Schedule

- Self-Explanation Technique

- Micro Steps

- Using Technology Wisley

Short sessions beat long marathons

You probably think longer sessions mean better memory.

Research shows short, spaced sessions usually produce stronger long-term recall than single long blocks. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Spacing forces your brain to rebuild a memory each time, which strengthens it. (“Temporal Spacing and Learning”)

That makes short sessions a powerful tool for memorizing math equations. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Try using many brief, focused sessions rather than one long cram.

Ten to fifteen minutes of work, repeated several times over days, is effective. (Rohrer and Taylor)

This supports math study habits that fit your schedule, not replace it.

Quick micro-study routine

- Learn the idea and do an immediate short recall. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- Wait 24 hours, then recall again for 5–10 minutes. (Lindquist et al.)

- Repeat a spaced recall three to four times across the week. (Lindquist et al.)

These small steps help with retaining math concepts because they interrupt forgetting. (“Forgetting Curve”)

Make retrieval your main weapon

When you try to pull an equation from memory, you practice retrieval, not passive exposure. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Testing yourself once strengthens memory more than rereading notes twice. (Rohrer and Taylor)

So begin practice by closing notes and writing equations from memory. (Lindquist et al.)

A short routine you can use tonight:

- Read the formula once.

- Close your notes and write it from memory.

- Compare and correct mistakes. (Rohrer and Taylor)

These actions train math memory techniques by forcing active recall on demand.

Chunk formulas into meaningful parts

Large formulas can overwhelm working memory. (“Distributed Practice”)

Break a formula into two or three named chunks you can rehearse separately.

For instance, name a quadratic’s three parts: coefficient chunk, middle-term chunk, constant chunk.

Once you retrieve each chunk, reconstruct the whole equation. (“Distributed Practice”)

Chunking reduces cognitive load and speeds recall for memorizing math equations. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Use flashcards the right way

Flashcards can be powerful when they force retrieval instead of passive review. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Design cards with a short prompt on the front and a compact equation chunk on the back.

Include a one-line reason why the chunk is there. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Flashcard routine (bullet list):

- Test yourself without looking at the back. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- Shuffle cards and retry after a short break. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- Revisit weaker cards more often within your spaced cycle. (Lindquist et al.)

This makes flashcards a tool for math study habits, not just note storage.

Mix problem types — don’t practice in a bubble

Practice similar problems in random order rather than in long single-type blocks. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Interleaving helps you decide which equation fits a new problem faster. (Rohrer and Taylor)

That flexibility is essential when an exam question looks different from practice sets.

Quick interleaving pattern: pick three problem types, rotate them during a 20-minute session.

Keep each problem short and active to force recall and choice. (Rohrer and Taylor)

This strengthens math memory techniques and transfers learning to new contexts.

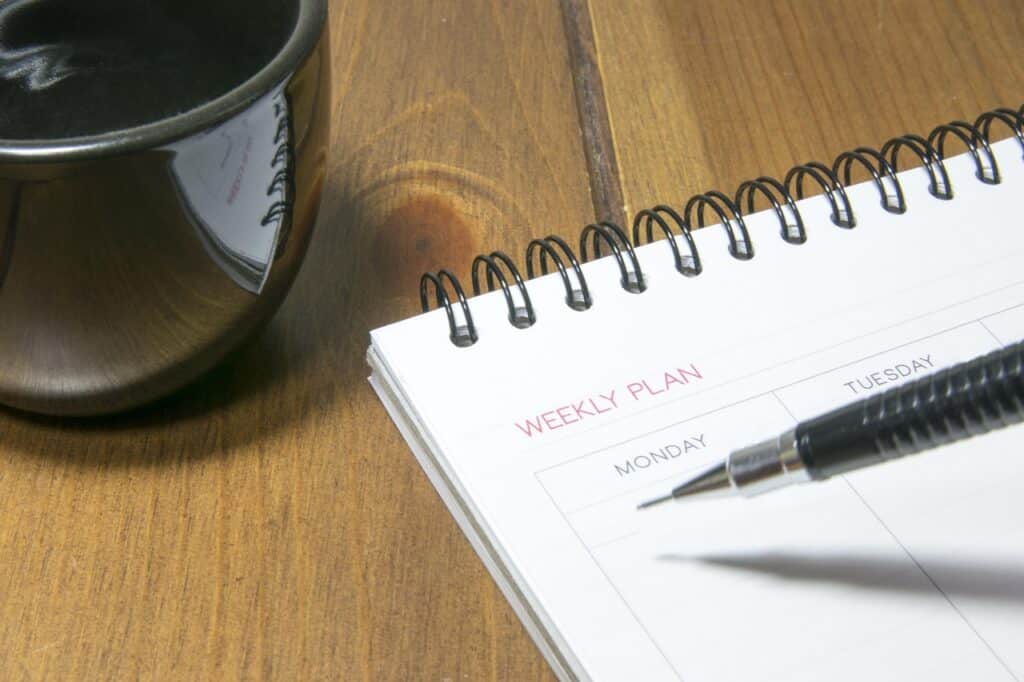

Design a weekly cycle that fits your life

A simple schedule beats a perfect but complicated plan.

Here’s a realistic four-step weekly cycle that follows spacing research. (Rohrer and Taylor; Lindquist et al.)

| Purpose | Session length | When |

|---|---|---|

| Learn + immediate recall | 10–15 min | Day 1 |

| Second recall | 5–10 min | Day 2 |

| Mixed practice | 15–20 min | Day 4 |

| Cumulative review + self-test | 15–25 min | Day 7 |

Follow this pattern for two weeks and you’ll likely see better retrieval. (Lindquist et al.)

This supports retaining math concepts more reliably than random study.

Use self-explanation to deepen recall

Explain each step aloud the way you would teach it to someone else.

Self-explanation links procedures to meaning, which strengthens the memory trace. (Rohrer and Taylor)

You don’t need an audience — talk through the “why” as you practice. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Pair an explanation with a one-sentence mnemonic for the hardest part.

Mnemonics give you a retrieval cue that points to the correct chunk. (“Distributed Practice”)

Together, these techniques improve memorizing math equations and reduce blind guessing.

When anxiety blocks retrieval, use micro-steps

Blanking on a formula happens to everyone.

Stop, breathe, and retrieve one chunk instead of the whole equation. (Lindquist et al.)

Small successful recalls lower anxiety and make bigger recalls easier. (Lindquist et al.)

Short exam-week checklist (bullet list):

- Replace one long study block with four short retrievals. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- Do one timed mixed problem set to practice under mild stress. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- Teach a friend one equation in two minutes to check clarity. (Lindquist et al.)

These steps build math study habits that tolerate pressure.

Use technology wisely — not as a crutch

Apps that implement spaced repetition can help, but use them to support active retrieval. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Avoid passive review modes that simply show cards without forcing recall. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Combine app review with handwritten practice and verbal self-explanation. (Lindquist et al.)

Digital tools are best when they fit your math memory techniques, not replace them.

Why this works — evidence summary

National assessments show long-run shifts in achievement, indicating teaching and practice matter. (National Center for Education Statistics)

Controlled lab and classroom studies find distributed practice and retrieval double or substantially improve retention for many tasks. (Rohrer and Taylor; Lindquist et al.)

Temporal spacing and repeated retrieval create durable memories by repeatedly reactivating and reconsolidating learning. (“Temporal Spacing and Learning”; “Forgetting Curve”)

Recent classroom trials showed spaced recall reduced forgetting of precalculus concepts months later. (Lindquist et al.; ERIC)

Scholarlysphere highlights several classroom implementations where frequent, low-stakes retrieval reduced forgetting and increased correct recall. (Lindquist et al.; ERIC)

Small habits that make big differences

Pick one anchor: after dinner, before bed, or after your commute.

Tie a five- to ten-minute recall practice to that anchor for two weeks.

Keep a one-line log: date, equation, correct recalls. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Seeing progress builds confidence and keeps you returning to practice.

Final quick tips you can use tonight:

- Convert one formula into a two-line cheat card.

- Test yourself for five minutes before bed. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- Explain a formula to a friend or to your phone’s voice recorder. (Lindquist et al.)

If you follow just a few of these tips consistently, you’ll boost your memorizing math equations ability and form lasting math study habits.

Step-by-step: Turn practice into results

7-step routine you can repeat

- Pick one equation you struggle with tonight.

- Read it once, then close your notes. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- Write the equation from memory, slowly. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- Say aloud why each part belongs there. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- Check mistakes and correct them immediately. (Lindquist et al.)

- Wait 24 hours and recall for 5–10 minutes. (Lindquist et al.)

- Repeat a spaced recall three to four times over the week. (Rohrer and Taylor)

This simple cycle uses retrieval and spacing to boost memorizing math equations.

It fits real evenings and keeps study short but effective. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Two habit anchors you can create

Anchor 1 — After dinner: five to ten minutes of recall.

Anchor 2 — Before bed: one quick test and one verbal explanation. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Tie practice to an existing habit so you don’t need extra motivation.

Small anchors build math study habits without big time costs. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Quick anchor checklist:

- Put flashcards by the dinner table.

- Set a two-minute alarm for pre-bed recall.

These tiny triggers help with retaining math concepts.

Daily micro-routines (practical templates)

Template A — Test prep (20 minutes total)

- 10 minutes: learn + write from memory. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- 5 minutes: short mixed problems. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- 5 minutes: correct and explain aloud. (Lindquist et al.)

Template B — Deep mastery (weekly cycle)

- Day 1: initial learning + immediate recall. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- Day 2: 5–10 minute retrieval. (Lindquist et al.)

- Day 4: mixed application practice. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- Day 7: cumulative self-test and correction. (Lindquist et al.)

Use the template that matches your test schedule.

Both emphasize retrieval and spacing over rereading.

How to break an equation into chunks

Step 1 — Identify 2–3 meaningful parts. (“Distributed Practice”)

Step 2 — Give each part a short label or phrase. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Step 3 — Practice retrieving each chunk separately.

Step 4 — Reconstruct the whole equation from those chunks.

Chunking reduces overload and helps you recall faster. (“Distributed Practice”)

Flashcard routine you can follow

- Front: a short prompt or mini-problem.

- Back: the equation chunk and a one-line reason. (Rohrer and Taylor)

- Test: force recall, then check.

- Spacing: revisit weaker cards sooner. (Lindquist et al.)

This keeps flashcards active, not passive.

Troubleshooting: what to do when you blank

Pause and breathe for 10 seconds.

Retrieve one chunk, not the whole equation. (Lindquist et al.)

If you still struggle, teach the equation aloud for one minute. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Small successes reduce anxiety and speed later recall. (Lindquist et al.)

Measure progress without stress

Keep a tiny log: date, equation, recalls correct out of three.

Track weekly — look for steady upward trends. (Rohrer and Taylor)

Celebrate small gains; they show that your math memory techniques are working.

Mini review of why this helps

Retrieval plus spacing repeatedly reactivate memory and strengthen it. (“Temporal Spacing and Learning”; “Forgetting Curve”)

Classroom trials show spaced recall reduces forgetting months later. (Lindquist et al.; ERIC)

National assessments suggest sustained practice and effective routines change outcomes. (National Center for Education Statistics)

You now have a concrete, repeatable plan to improve at memorizing math equations.

Which one step will you start with tonight?

References

Rohrer, Doug, and Kelli M. Taylor. “The Effects of Overlearning and Distributed Practice on the Retention of Mathematics Knowledge.” Applied Cognitive Psychology, vol. 20, 2006, pp. 1209–1224. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED505642.pdf

Accessed 26 Nov. 2025

Lindquist, Diane S., Brenda E. Sparrow, and Joseph M. Lindquist. “Spaced Recall Reduces Forgetting of Fundamental Mathematical Concepts in a Post-High School Precalculus Course.” Instructional Science, vol. 52, 2024, pp. 859–878. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-024-09680-w

Accessed 26 Nov. 2025

“Spaced Recall Reduces Forgetting of Fundamental Mathematical Concepts in a Post High School Precalculus Course.” ERIC, 2024. https://eric.ed.gov/?ff1=subMathematics+Instruction&id=EJ1440773

Accessed 26 Nov. 2025

National Center for Education Statistics. The Nation’s Report Card: Mathematics 2009. U.S. Department of Education, 2010. https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/pubs/main2009/2010451.aspx

Accessed 26 Nov. 2025

National Center for Education Statistics. The Nation’s Report Card: Mathematics 2007. U.S. Department of Education, 2007. https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/pubs/main2007/2007494.aspx

Accessed 26 Nov. 2025

“Spacing Effect.” Psychological Science Observer, Association for Psychological Science, 2006. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/temporal-spacing-and-learning

Accessed 26 Nov. 2025

“Distributed Practice.” Wikipedia, last edited 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distributed_practice

Accessed 26 Nov. 2025

“Forgetting Curve.” Wikipedia, last edited 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forgetting_curve

Accessed 26 Nov. 2025